Sausage appliance

I can't think of any other recording artist equally responsible for just as many songs that I love as ones that I loathe as Morrissey. Nor someone whose output I have been somehow unable to throw away down the years despite a substantial portion it being quite horrendous.

There was a point when I eagerly snapped up each and every one of the man's releases, despite it largely coinciding with what is commonly held to be the most fallow of all his fallow periods (1994-7), almost all of which I subsequently listened to once and never again. Yet they still all sit there on my shelves, challenging me to give them a new home in the nearest bin bag, daring me to play them for a second time.

Back when he was properly good (and not merely sentimentally good, as he appears to be now) I relied for my education as to the life and work of Morrissey upon my friend David, whom if memory serves correctly had fostered an interest in the man around the time some of The Smiths' singles were being re-released on CD in the summer of 1992. A few months later began one of those characteristic instances of osmosis, unique to the British school 6th form system, where one person begins to absorb somebody else's collection of tastes and interests in return for a suite of their own (in my case, The Beatles).

As much as there can ever be one defining moment in such a process, I would cite it as being when David leant me his vinyl copy of The Smiths' 'Hatful Of Hollow' LP, a moment fixed in my brain thanks to it also falling on the date of a spectacularly dreadful school production of selected works of the German playwright Bertold Brecht for which I was haplessly conducting the music, and for all the fuses tripping in my family home that night leaving us temporarily without any electricity. Meaning, among other things, I couldn't play the aforementioned record until the following morning.

When I did, there was something immediately striking about the wistfully cynical, broodingly romantic whining of lines like "England is mine, and it owes me a living - ask me why and I'll die" and "I would love to go back to the old house, but I never will", set to such curiously contemporary yet evocative musical tapestries, that I have to confess I found immediately irresistible.

At the time I guess I was happy to let myself stumble upon a new hook upon which to helpfully hang all my teenage, well, hang-ups. In retrospect I was probably glad to have been presented with a form of music that so effortlessly married profound literary lyricism and subtle musical craftsmanship - two qualities I had sought to enjoy, often separately but rarely together, throughout my life.

For a long time afterwards I pursued an interest in Morrissey that extended into his increasingly patchy and ultimately pathetic solo career. It was a strange experience, being an ostensible fan of somebody embarked upon - what seemed to me - a path that was leading towards mutually assured extinction.

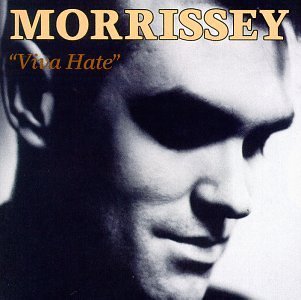

His first solo album 'Viva Hate' had been superlative and still remains his best work: beautifully sung, sympathetically produced (by Stephen Street), supremely melodic (ditto) and above all brilliantly fresh and forward-looking. Then came endless singles of varying quality, the stop-gap compilation 'Bona Drag', the half-wonderful, half-woeful 'Kill Uncle', the YTS rockabilly right-wing roustabout 'Your Arsenal', the furore over Johnny Rogan's biography The Severed Alliance (dubbed by its subject The Sausage Appliance) and, in 1994, 'Vauxhall And I', what seemed at the time to be evidence of, if not a return to form, then at least consistency.

But then everything went horribly wrong: pointless singles about East End bruisers and window cleaners, an obsession with working class thuggery, too many songs without any tunes, even more with just downright shit tunes, the sense of merely recycling the same concerns and themes (and chord sequences) over and over, the retreat into American isolationism and semi-retirement. Plus there was the court case brought by former Smiths drummer Mike Joyce about unpaid royalties, during which the judge labelled Morrissey as being "devious and truculent".

I abandoned any real or resolute interest in the man round about 1997 and the bizarre 'Maladjusted' album, the most indifferent yet needling album he had then been motivated to make. And that's the way it has stayed, despite Morrissey's 'comeback' during the last couple of years, his run of top ten hits, his ostensibly blistering live performances, his waspish outbursts, and his embrace by a new breed of critics and audiences alike.

Yet I still cannot bring myself to exile those traces of his pre-revival, post-peak oeuvre from my possessions. I can only conclude this is partly because of their anachronistic status, partly because they always make for great talking points when I'm reminiscing with David, and partly because of how they represent the end point of a particular kind of relationship which wound its mercurial way through much of the 1990s and which will always remind me of the places, faces and mood of those times.

And ultimately some bits of the past are too present, or rather too prescient, to ever get rid of.

Let me see all my old friends

Let me put my arms around them

Because I really do love them

Now does that sound mad?